Part 3: Florida’s Regulatory Landscape

While Part II explored how the internal dynamics of the temp industry concentrate control in the hands of agencies and host employers at the expense of workers, those practices don’t exist in a vacuum. They are reinforced—and, in some cases, enabled—by the state’s regulatory framework. In Florida, weak enforcement, sweeping preemption laws, and employer-friendly labor policies create an environment where exploitation is not merely possible but predictable.

This section begins with the Florida’s Labor Pool Act (FLPA), the state’s most direct and comprehensive attempt to regulate day-labor and temporary work. The FLPA offers crucial safeguards, such as limits on predatory fees and the right to accept permanent employment with a host company, but its narrow scope and limited enforcement leave most temp workers unprotected. From there, we examine the broader framework shaping labor conditions across Florida: a hollow enforcement system that fails to hold employers accountable, expansive preemption laws that block local governments from setting stronger standards, and “right-to-work” policies that weaken collective bargaining power and embolden employers to suppress worker organizing.

Taken together, these overlapping systems reveal how Florida’s regulatory architecture privileges employer flexibility over worker security. They help explain why even major advocacy victories, like the defense of the FLPA, are insufficient on their own to transform the industry, and, as we explore in Part IV, why building durable power for workers with records requires going far beyond reforming existing laws.

Florida’s Labor Pool Act

In 2025, Florida lawmakers introduced HB 6033138 and SB 1672139 to repeal the FLPA, a 1995 law providing rare, industry-specific protections for blue-collar temp workers who find work through labor pools and, likely, traditional temp agencies that assign work out of a labor hall for positions that are temporary in nature. The Act guarantees minimum wage, pay transparency, caps predatory fees, and guarantees workers the right to accept permanent employment with host companies, and other basic workplace protections.

Proponents of repeal, backed by lobbying groups such as the National Federation of Independent Business and temp agencies like Pacesetter Personnel Services, claimed the Act was “duplicative” of federal and state laws.140 Pacesetter itself had previously faced a class action lawsuit alleging serious violations of the FLPA, including failing to ensure access to water and restrooms for workers.141 (The lawsuit was later dismissed, though the judge left the door open for plaintiffs to refile.142)

Worker advocates, led by Beyond the Bars, countered that the FLPA fills critical gaps “where federal law is silent or inefficient,” and that existing state law offers few comparable protections. Following relentless mobilization, public education, and direct advocacy, the repeal effort was successfully defeated in April 2025.143

While the FLPA remains an essential safeguard, it falls far short of ensuring dignity or safety for most blue-collar temp workers. It relies exclusively on private enforcement, with no dedicated state oversight, and achieving robust reforms, like those enacted in 2023 under Illinois and New Jersey’s Temp Worker Bill of Rights, remains politically difficult in Florida’s current climate. Compounding this, the state’s sweeping preemption policies prevent local governments from adopting stronger standards.

The remainder of this section examines these structural barriers and considers what it will take for workers and advocates to overcome them.

State Preemption

State-level preemption, a legislative power exercised by a state government to prevent or override laws passed by its own lower-level governments, like counties and cities, has become a defining feature of Florida’s state legislature. In the past five years, state legislatures have have used preemption to block dozens of local efforts to strengthen worker and tenant protections locally.

Take, for example, WeCount!’s Que Calor campaign to protect outdoor workers in Miami-Dade County from excessive heat. Research estimates that over 70 percent of heat-related deaths coincide with a worker’s first week on the job.144 In 2024, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed legislation that prevented local governments from passing their own heat protection standards that would help ensure safe conditions for outdoor workers. This effectively blocked efforts on the agenda in Miami-Dade County, which had been preparing to pass the nation’s first municipal heat standard, including heat safety education, mandatory water breaks, and shade provisions for 100,000 agriculture and construction workers.145

This preemption model extends far beyond heat protections. Notably, while Florida has made some progress in raising its statewide minimum wage,146 it has long prohibited municipalities from creating their own minimum wage standards. In 2024, the state took this preemption even further, adding new language prohibiting municipalities from requiring companies holding public contracts to pay more than the state minimum.147 Such restrictions make it harder for local governments to enforce higher wage standards for temp agencies, though it may be possible for them to require other sorts of worker protections.

The state also prohibits local governments from mandating fair scheduling, requiring paid sick or family leave, or setting stronger labor standards for public contracts. These restrictions make it nearly impossible for local governments in Florida to establish fairer standards for temp agency workers, even when communities, employers, and local officials agree that higher protections are needed. By concentrating power at the state level and stripping it from local governments, labor standards become increasingly disconnected from local need, leaving temp workers with records trapped in a race to the bottom.

Inadequate State and Federal Enforcement Mechanisms

Nothing illustrates Florida’s weak worker protection infrastructure more clearly than the persistence of wage theft. Florida has one of the nation’s highest rates of wage theft, disproportionately affecting low-wage workers.148,149 Workers in the state are much more likely to be paid less than minimum wage,150 and industries such as construction, transportation, and warehousing—which rely heavily on temporary labor—are among those most affected.

National data confirms that temp workers are particularly vulnerable. A February 2024 survey by the National Employment Law Project (NELP) and partner organizations found that 24 percent of temp workers reported having wages stolen by their employers.151 Yet only a small fraction of those affected ever file complaints or recover their lost pay. Even so, temp agencies consistently find themselves on the list of 20 “Low Wage, High Violation” industries compiled annually by the U.S. Dept. of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division.152

Despite the scale of the problem, Florida’s capacity to enforce labor laws is woefully inadequate. The state has no Department of Labor, and the Attorney General, its only office authorized to enforce the minimum wage, rarely acts.153

Workers can file complaints with the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), but relying on the federal agency alone leaves enormous gaps. The DOL’s resources are stretched across 50 states and millions of workplaces, making proactive, industry-wide investigations nearly impossible, even under labor-friendly federal administrations.

From the perspective of individual workers, the process is also daunting. Filing a federal wage claim typically requires detailed documentation, such as pay stubs, hours worked, and employer information, that temp workers often lack access to. Investigations can take months or years, and workers who file complaints risk retaliation or blacklisting, especially in industries with little union presence. As a result, most workers simply give up before filing or accept losses they cannot afford to contest.

Since 2003, the DOL has recorded approximately 8,300 wage theft violations affecting 6,239 workers in Florida’s temp industry. Many of these cases involved hundreds of incidents per investigation. Altogether, these cases resulted in just over $4.1 million in recovered wages and just over $312,000 in civil penalties.154 That comes to an average of fewer than 300 Florida workers per year who have been able to recover some wages through the federal wage and hour process.

Florida also lacks a state-level agency to oversee workplace safety. States may establish their own occupational safety and health plans, referred to as a “state plan”,” that meet or exceed federal OSHA standards, but Florida has chosen not to do so. Since 2015, federal OSHA has issued only 31 citations to temp agencies in the state, collecting just $252,992 in penalties after settlements reduced fines by more than a quarter. (See Appendix)

These low figures reflect OSHA’s limited inspection resources, the pervasive fear among temp workers of retaliation if they report unsafe conditions,155 and the fact that OSHA enforcement typically targets host employers rather than temp agencies. As a result, many temp workers fall through the cracks of the “joint employer” system. This shared responsibility model often results in shared neglect, no single entity is held accountable for protecting workers’ safety.

Without a state agency dedicated to protecting workers or the authority for local governments to fill that gap, Florida’s enforcement system effectively outsources accountability to the very agencies least equipped to deliver it.

Florida’s “Right to Work” Law

Florida’s status as a “right to work” state, which has been enshrined in the state constitution since 1944,156 further weakens the ability of workers to organize and bargain collectively. Under right-to-work laws, employees cannot be required to pay union dues, even when they benefit from a union contract. This arrangement drains unions of resources, diminishes their bargaining power, and emboldens employers to resist collective action.

With union density in Florida among the lowest in the nation (just over 5 percent157), temp agencies and their clients operate in a labor environment largely devoid of countervailing power. For temp workers, who already face instability, employer retaliation, and complex joint-employment structures, right-to-work laws make formal union representation exceedingly difficult to obtain. The result is a labor market where employers enjoy both flexibility and impunity, while workers remain atomized and disposable.

Legal Obstacles to Organizing Temp Workers

Finally, the barriers to collective action are steep. Even outside the temp industry, U.S. labor law makes organizing difficult, whether that means forming a union, joining an existing union at your workplace, fighting for a safe workplace, combatting discrimination, or working together to address systematic wage theft. While there are laws on the books intended to protect these activities, enforcement is often too slow, and penalties too anemic, for these protections to have much power.

Temp workers are especially exposed. As described earlier in this report, the close relationship between the temp industry and the carceral system amplifies workers’ vulnerability to retaliation and job loss. As one Beyond the Bars member, Charles, explained, “If you speak up about a problem, you’re just going to lose your job.”

Moreover, temp agencies and host employers together engage in practices that make collective action more difficult. Agencies can simply stop dispatching temp workers who engage in organizing or transfer them to distant worksites.158 During union drives, employers may reclassify permanent employees as temps, under threat of termination, to dilute union strength. They may illegally replace, or threaten to replace, pro-union workers with agency temps. They may manipulate a union election by contesting bargaining unit definitions, depending on how friendly the temp workforce is to the union.

When temps are against the union, they may argue that the workers should be included in the bargaining unit, and when temps are supportive of the union, they may argue that they can’t be represented together in the same “multi-employer” bargaining unit without the consent of the temp agency, which a rare occurrence.159

Even within existing union workplaces, employers leverage temp labor to undermine collective power. By hiring a layer of permatemps, employers create a two-tier system that splits the workforce in a present-day version of “divide and rule.” They may threaten to outsource jobs to temp agencies or bring in replacement workers ahead of contract negotiations, in hopes of pressuring unions into trading looser restrictions on temps in order to win improvements on wages, benefits, or other workplace protections. Because U.S. law allows employers to permanently replace workers who strike for economic reasons,160 these practices further erode unions’ negotiating power and increase the economic pressure on union members.161

Still, history shows that contingent workforces can be organized, despite many facing similar obstacles to those above. Market-wide agreements for commercial office janitors, pooled benefit funds coupled with best-in-class training in the building trades, and recent efforts to organize ride-share drivers all demonstrate how creative strategies can overcome structural barriers, even in right-to-work states.

Moreover, some directly hired workers were once temps themselves or have family members working through temp agencies, creating natural solidarity that can be built upon.

And, while the current political climate is hostile to workers’ rights, the high degree of control that host employers reserve over temp workers makes them joint employers of temp workers.162 The NLRB clarified in Miller & Anderson that for temps jointly employed by a client, those temps and the client’s permanent employees can join a single bargaining unit so long as they share a community of interest.163

While in 2020, the Trump administration narrowed the joint-employer standard to require a showing that the joint employer reserves and exercises “substantial direct and immediate control over one or more essential terms or conditions of” employment,164 the substantial direct control typically exercised by host employers is sufficient to establish joint employer status in most cases.165

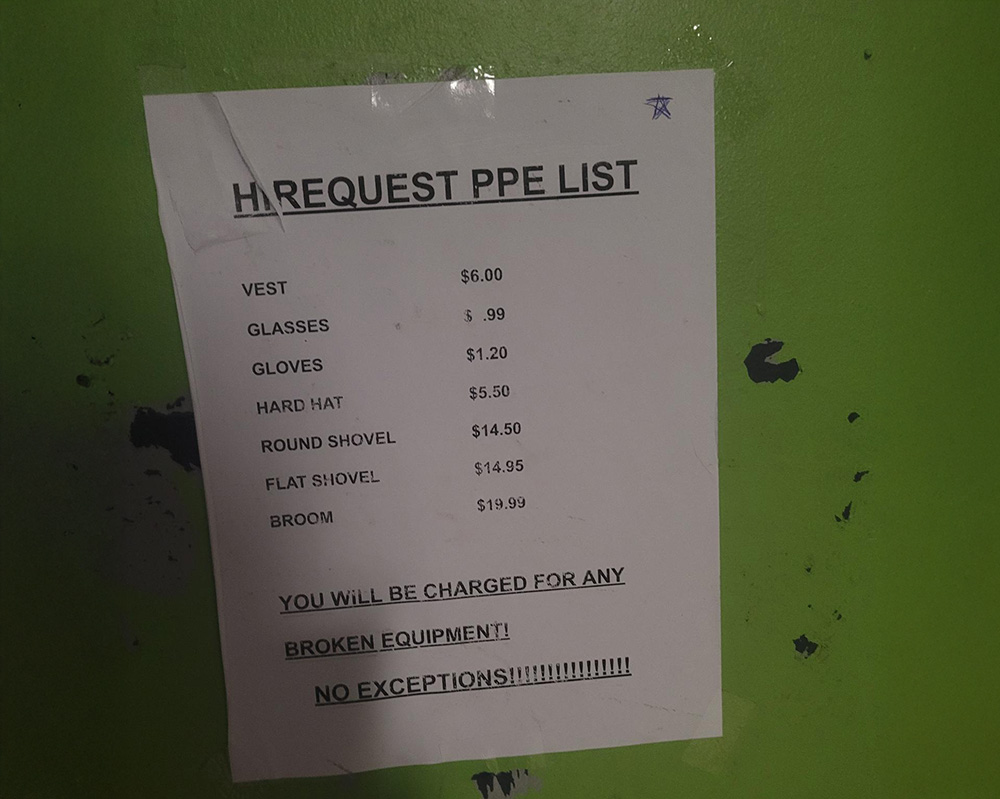

Despite the FLPA’s protections, enforcement remains challenging. Documents from Florida labor pools reveal business practices that test the law’s boundaries. HireQuest’s price list for Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) (top right of p. 65) warns workers they will be charged for “ANY BROKEN EQUIPMENT! NO EXCEPTIONS!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!” The FLPA permits agencies to charge workers only when they “willfully fail to return” temporarily provided items—not for equipment that breaks during normal use.

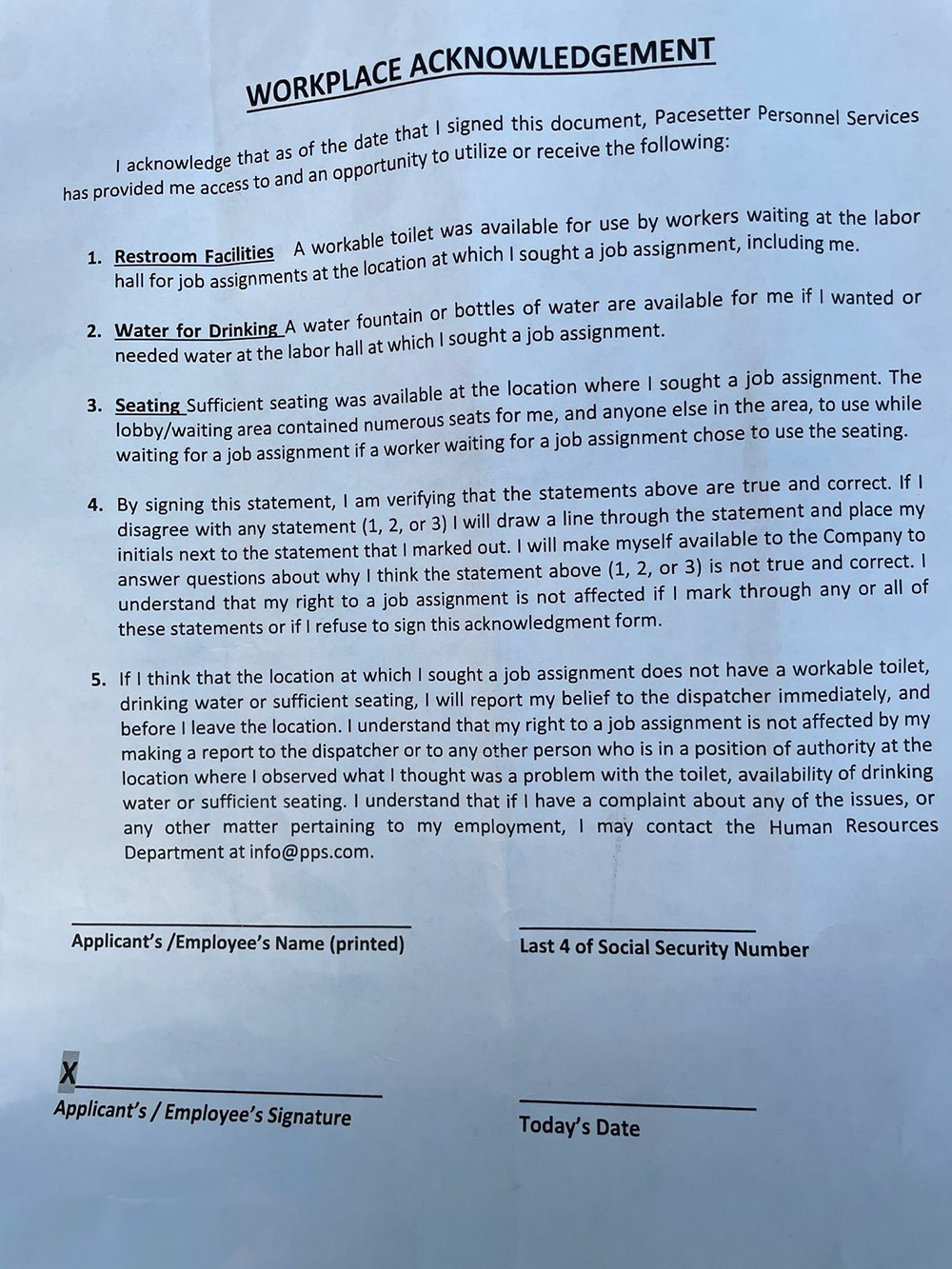

Pacesetter Personnel Services requires workers to sign acknowledgments (bottom left of p. 65) confirming access to restrooms, drinking water, and seating—some of the very workplace basics Pacesetter was accused of denying in previous lawsuits. While the form states that signing doesn’t affect job assignments, workers facing fierce competition for limited positions may feel pressured to sign regardless of actual conditions.

Meanwhile, contract terms from one staffing agency (top left of p. 65) prohibit host employers from hiring temp workers without the agency’s written approval, while other contracts (not pictured) demand payment for 520 billable hours of work before a worker can be hired permanently. Both practices appear to violate the FLPA, which explicitly states: “No labor pool shall restrict the right of a day laborer to accept a permanent position with a third-party user to whom the laborer is referred for temporary work, or to restrict the right of such a third-party user to offer such employment to an employee of the labor pool. However, nothing shall restrict the labor pool from receiving a reasonable placement fee from the third-party user.”

These documents illustrate a fundamental problem: the FLPA relies entirely on private civil lawsuits rather than a dedicated state enforcement body. Moreover, the law includes no provision for attorneys’ fees—meaning plaintiffs’ attorneys have little financial incentive to take on cases for low-wage workers whose individual damages may be modest. As a result, few lawsuits have been filed under the FLPA, and questions about the precise contours of workers’ rights under the law remain undecided by courts. Labor pools thus operate with minimal accountability, leaving workers to navigate a system where violations are commonplace yet meaningful recourse is scarce.

Footnotes

- 138. H.B. 6033, Labor Pool Act, 2025 Leg., Reg. Sess. (Fla. 2025) (died on Second Reading Calendar, June 16, 2025), https://flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2025/6033.

- S.B. 1672, Labor Pool Act, 2025 Leg., Reg. Sess. (Fla. 2025) (died in Fiscal Policy, June 16, 2025), https://flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2025/1672.

- Mitch Perry, “Bill that would repeal Florida Labor Pool Act advances to full House,” Florida Phoenix, April 22, 2025. https://floridaphoenix.com/2025/04/22/bill-that-would-repeal-florida-labor-pool-act-advances-to-full-house/; H.B. 6033, 2025 Leg., Reg. Sess. (Fla. 2025), https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2025/6033; S.B. 1672, 2025 Leg., Reg. Sess. (Fla. 2025), https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2025/1672/ByCategory

- Shane Villarino, et al. v. Kenneth Joekel, et al., No. 24-11124 (11th Cir. 2025).

- Villarino, No. 24-11124.

- McKenna Schueler, “Worker advocates manage to kill Florida bill that would have eliminated labor protections for temp workers,” Orlando Weekly, May 6, 2025, https://www.orlandoweekly.com/news/worker-advocates-manage-to-kill-florida-bill-that-would-have-eliminated-labor-protections-for-temp-workers-39449957. McKenna Schueler, “Last Week in Florida Politics: Anti-worker Bills on the Move (Week 7 of Session),” Caring Class Revolt, https://caringclassrevolt.substack.com/p/last-week-in-florida-politics-anti, April 20, 2025.

- OSHA, Prevention: Protecting New Workers, DOL, https://www.osha.gov/heat-exposure/protecting-new-workers.

- Aliya Uteuova, Nina Lakhani, and Michael Sainato, “Florida passes ‘cruel’ bill curbing water and shade protections for workers,” The Guardian, March 8, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/mar/08/florida-bill-extreme-heat-worker-protection.

- Briana Trujillo and News Service of Florida, “Florida minimum wage increases to $14 an hour on Sept. 30,” NBC 6 South Florida, July 31, 2025, https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/florida-minimum-wage-to-increase-to-14-an-hour-on-sept-30/3669918/.

- Economic Policy Institute, “Workers’ rights preemption in the U.S. (Florida Minimum Wage),” https://www.epi.org/preemption-map/, accessed August 28, 2025. See also Fla. Stat. § 218.077.

- NBC2 News, “Florida Ranks among top states for wage theft, $16.5M owed to workers, Gulf Coast News - Fort Myers, Florida (Dec. 27, 2024) https://www.gulfcoastnewsnow.com/article/florida-top-states-wage-theft/63292454#:~:text=Share,-Copy%20Link&text=A%20study%20has%20revealed%20that,2021%2C%20impacting%20almost%2010%2C000%20workers.; https://www.epi.org/publication/employers-steal-billions-from-workers-paychecks-each-year/

- David Cooper & Teresa Kroeger, “Employers steal billions from workers’ paychecks each year,” Economic Policy Institute, May 10, 2017, p. 151, https://www.epi.org/publication/employers-steal-billions-from-workers-paychecks-each-year/

- Cooper & Kroeger, “Employers steal billions.”

- “1 in 4 Temp Workers Reports Wage Theft, New Survey Finds,” In These Times, February 10, 2022, https://www.nelp.org/1-in-4-temp-workers-reports-wage-theft-new-survey-finds/.

- U.S. Dept. of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, “Low Wage, High Violation Industries,” https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/data/charts/low-wage-high-violation-industries, accessed August 26, 2025.

- Alexis Tsoukalas et al., “Florida Policymakers Need to Reassess How the Minimum Wage is Enforced,” Florida Policy Institute (Mar. 2021), https://www.floridapolicy.org/posts/florida-policymakers-need-to-reassess-how-the-minimum-wage-is-enforced.

- U.S. Department of Labor Enforcement Data, https://enforcedata.dol.gov/views/search.php, NAICS Code 561320, data current through September 23, 2025.

- U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Inspections Within Industry (data current through 3/14/2025), https://www.osha.gov/ords/imis/industry.html, for NAICS Code 561320 within the state of Florida.

- Fla. Const. art. I, § 6.

- BLS. (2025, January 28). Table 5. Union affiliation of employed wage and salary workers by state [Data table]. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.t05.htm

- Erin Hatton, “Temporary Weapons: Employers’ Use of Temps Against Organized Labor,” Industrial & Labor Relations Review, January 1, 2014. Interview with George Gonos, March 18, 2025.

- Hatton, Temporary Weapons.

- National Labor Relations Board, “The Right to Strike,” https://www.nlrb.gov/strikes. National Labor Relations Act, Section 502, https://www.nlrb.gov/guidance/key-reference-materials/national-labor-relations-act.

- Hatton, “Temporary Weapons,” p. 101-102.

- Andrew Elmore, Kati L. Griffith & Sachin D. Pandya, “Presuming Justice for Temp Workers,” 67 Wm. & Mary L. Rev., at *43, Oct. 7, 2025, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5556759.

- Andrew Elmore, “Mobility and Power in Temp Work,” 51 B.Y.U. L. Rev., 101, 173 (forthcoming 2025) (citing Miller & Anderson, 364 N.L.R.B. No. 39 (2016)).].

- 29 C.F.R. § 103.40(a).

- See Cognizant Tech. Sols. U.S. Corp. & Google LLC, Joint Emps. & Alphabet Workers Union—Commc’ns Workers of Am., Loc. 1400, 372 NLRB No. 108 (July 19, 2023) (finding that Google jointly employed its temp agency’s workers under this test because it “possesses and exercises such substantial direct and immediate control over the employees’ s

Want future reports + tools?

Subscribe to The Work Release to get new publications, campaign updates, and worker stories.